THE GARDIAN

As well as helping the economy recover after the Covid-19 pandemic, new jobs in clean-electricity generation and low-carbon heating solutions could help the UK meet its net-zero targets

by Anna Turns

Jobs that have a direct, positive impact on the planet traditionally involve renewable energy, electric transport, energy efficiency or nature conservation. But right now, as more sectors transition to low-carbon models, every job has the potential to become “green”.

With unemployment rising due to the pandemic, there’s now a chance to reconfigure the jobs landscape while putting the environment centre stage. The government’s £160m Build Back Greener investment scheme aims to create 2,000 new construction jobs to manufacture offshore wind turbines and upgrade ports.

How and where will demand increase as the UK transitions to a net-zero economy?

By 2030, there could be 694,000 green jobs in the low-carbon and renewable energy sector across England, rising to more than 1.18m by 2050. There’s enormous potential for green growth.

Research by the Institute for Public Policy Research suggests that more than 200,000 jobs could be created in energy efficiency by 2030, and 70,000 jobs in offshore wind alone as soon as 2023, while Thrive Renewables estimates that onshore renewables could deliver 45,000 new jobs by 2035. Regionally, opportunities vary. In north-west England, new jobs focus on increasing wind capacity, while London’s green jobs will mostly be in the financial, IT or legal industries.

Why do we need a decarbonised future?

Economist Kate Raworth, from the University of Oxford’s Environmental Change Institute, believes that we need a decarbonised economy far sooner than 2050. According to Raworth, the economy should urgently be redesigned so that resources aren’t wasted. That, she says, requires serious innovation: “Our future economy will thrive on reusing, repairing, refurbishing, remaking and repurposing – this transformation will create new kinds of creative and purposeful jobs.”

Reimagining the economy

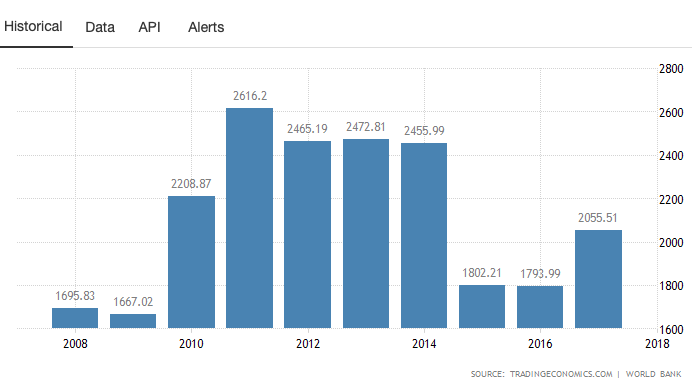

In 2018, the UK government projected that the low-carbon economy could grow by 11% per year up to 2030. That’s much higher than the projected growth rate for the overall economy. Globally, emergency Covid-19 economic rescue packages already total more than £6tn in G20 nations. In fact, the transition to net-zero emissions and investment in low-carbon sectors can aid recovery from Covid-19.

“Green jobs help us realise environmental goals and contribute to livelihoods – it’s not new, but it is an idea we are now paying more attention to,” says Jennifer Allan, a lecturer in politics and international relations at Cardiff University, who describes climate action as an “economic multiplier”, because creating green jobs helps mitigate the ecological crisis.

In June 2020, Boris Johnson earmarked several billion pounds to upgrade the energy efficiency of public buildings and homes, and for carbon capture technology to remove harmful carbon emissions from the air. As a result, UK industry will also receive £350m investment to cut carbon emissions in sectors such as transport and construction.

By comparison, France is planning to invest one third of its €100bn (£90bn) post-Covid economic stimulus on greening the economy – more than any other big EU country – but critics insist that even this falls short of what is necessary for a step change. Germany’s €130bn recovery budget focuses on climate-friendly industries and aims to support green infrastructure and technologies with at least €40bn spending in this area.

Energy efficiency: a win-win scenario

A report by the Energy Efficiency Infrastructure Group suggests that decarbonising the UK’s housing stock will create 100,000 jobs annually over the next decade. Homeowners in England can now apply for vouchers worth up to £5,000 to make their homes more energy efficient under the new government scheme for green home grants. Retrofitting homes could not only result in more efficient energy consumption but also create green jobs for those installing double glazing, insulation or air-source heat pumps.

So home retrofits are a major win-win. “It’s about a systemic shift, not isolated innovations,” explains Eliot Whittington, director of policy at the Cambridge Institute for Sustainability Leadership (CISL).

A future fuelled by renewables?

By 2035, new diesel, petrol or hybrid cars will no longer be sold in the UK, but cost remains a barrier to switching to electric vehicle (EV) production because big upfront investment is required. As industries evolve, upskilling of the workforce is essential, too – individuals will need retraining and financial support to make that viable.

For clients of Nick Daniel, head of energy and climate change at the recruitment firm Acre, the climate emergency has become a board-level priority with many new sustainability roles being classified as “business critical”, despite other hiring having been frozen. Daniel believes that unless organisations invest in sustainability credentials, they’ll get “left behind in the race against climate change”.

Is the future green?

A green recovery can boost the economy, protect the environment and invigorate the workforce. Demand for sustainable business is rapidly increasing according to Paula McGinnell, from Cyan Finance, which provides finance to businesses and projects in the green, sustainable and socially positive economy. “Green jobs build resilience, and the economic opportunity they provide is the largest we’ll see in our lifetime,” she says.

Alethea Warrington, a campaigner at the climate action charity Possible, says that considered, long-term investment by the UK government in clean energy, green transport and warm homes would be “the best medicine for the ailing UK economy right now”.

To search for all the latest green jobs visit Guardian Jobs

- This article was amended on 20 October 2020 to correct Nick Daniel’s name

Leave A Comment