Mongabay

- If Brazil shifts to a low carbon economy, carbon emissions would be cut by a third while also creating jobs, benefiting economic growth and infrastructure, according to a recent report by the World Resources Institute.

- Brazil’s post-COVID-19 economic recovery plan could provide an opportunity to implement long-term solutions across multiple sectors that could reduce carbon emissions and Amazon deforestation.

- Study authors hope that the economic benefits of the plan will push the current Jair Bolsonaro administration to adopt a green agenda, even if conservation is not a priority.

- “Climate denial is at a peak, but cost-benefit will be the leading decision-maker, whether or not it benefits the environment.… Due to post-COVID-19 economic recovery plans, we have a window of opportunity that will close in a year and a half or less.” — World Resources Institute Climate Policy Director Carolina Genin.

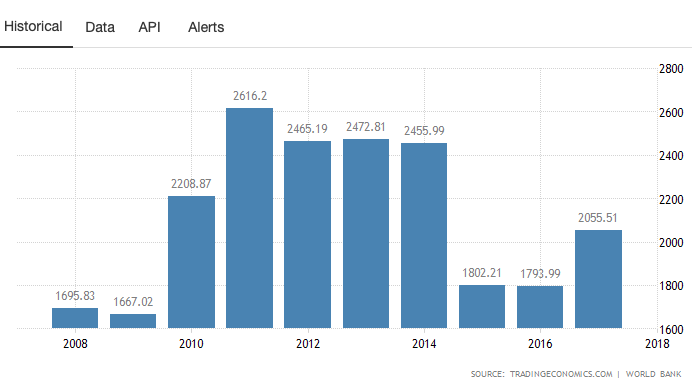

Shifting to a low carbon economy could boost Brazil’s economic growth and reduce carbon emissions by up to 33%, a new study led by the World Resources Institute (WRI) finds.

Investments into greener industry, energy and agriculture, according to the report published this August, could generate an extra US $325-$525 billion in GDP over the next ten years, while also reversing damage to Brazil’s environmental reputation, improving access to international investments and green bonds.

“We went into this asking if there would be a trade-off, protecting the climate in detriment to the economy, or if it’s a win-win situation,” WRI Climate Policy Director Carolina Genin told Mongabay. “What we found was that the low carbon scenarios were all better than business-as-usual.”

Under Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro, deforestation rates and Amazon fires are soaring, environmental agencies have been defunded, regulations have been drastically reduced, and climate scientists have been routinely sacked allegedly for publishing data on deforestation. His administration has also green-lighted illegal farms on indigenous lands and is pushing hard to open conservation units and indigenous reserves to mining and agribusiness.

But as Brazil prepares its plan for economic recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic, the benefits of adopting climate-friendly measures offer a glimpse of hope in an otherwise bleak financial future.

“Climate denial is at a peak, but cost-benefit will be the leading decision-maker, whether or not it benefits the environment. What we’re offering is an exit plan,” Genin said. “Due to post-COVID-19 economic recovery plans, we have a window of opportunity that will close in a year and a half or less.”

Can Bolsonaro’s Brazil go green?

Among its proposals, the WRI report urges the recovery of degraded pastures, building railways, and installing electric buses in Brazil’s public transit system — marrying long-sought goals to improve the country’s infrastructure with low carbon solutions.

The authors say that low carbon measures are more likely to be adopted by Bolsonaro now, as the government works urgently to produce a viable COVID-19 economic recovery plan, noting that the implementation of environmental goals could open up new economic markets and create two and a half million jobs over the next decade, while also boosting Brazil’s tarnished international reputation, reducing the risk of future censure and loss of investments.

“We know the vice-presidency and people in the technical ranks of the government were receptive,” said Roberto Schaeffer, an expert in energy economics at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro who contributed to the report. “To a point, we were surprised, but everyone wants to see a way out of this crisis.”

But for Marcio Astrini, the head of the Brazil-based environmental think tank Climate Observatory, there is reason to be skeptical. “It’s very difficult to believe that this government will adopt any sort of environmental agenda to conduct its policies — a government where the president, the foreign minister and others are climate deniers,” he told Mongabay. “Implementing strategic projects requires people in power who want to serve the country’s medium to long term interests, which is definitely not the case with this government.”

While Brazilian Economy Minister Paulo Guedes champions a strict austerity plan, other economists are clamoring for environmentally-friendly investments, causing a national policy tug-of-war between spending and austerity.

Persuading the current government to make these environmental investments won’t be easy agrees Dalia Maimon, a head professor of economics specializing in sustainability and social responsibility at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro. “There is talk about public-private partnerships, but if the private sector isn’t investing, it will need to come out of federal accounts — and it isn’t likely under the current minister,” she said.

Last month, 17 Brazilian former finance ministers and central bank directors signed a letter advocating for a transition to a low carbon economy. “Long term impacts of fiscal action will be more about how the money is spent than the volume of public spending, stimulating action on fronts that leverage Brazil’s comparative advantages and contribute to long-term economic productivity and job creation,” they wrote in the July 14 letter.

Increased pressure to curb deforestation and make Brazil’s commodities supply chains more sustainable coming from international investors and key importers of Brazilians goods could push decision-making into a corner. “Leaders may be forced to swallow this [greener development pill] whether they want to or not,” said Schaeffer.

Higher productivity, lower carbon emissions

Improving productivity is a cornerstone of the WRI report, as it seeks common ground between agribusiness and industrial interests and the environment.

A program to recover degraded pastures would cost US $4.5 billion. According to WRI’s plan, that investment could be earned back in six and a half years of increased productivity, while simultaneously decreasing deforestation pressures. “Just the tax revenue from this investment would total 742 million reais (US $134 million), which could help the government with their budget deficit,” said Viviane Romeiro, the lead researcher behind the WRI study.

But not all of the report’s proposals are without controversy.

The authors, for example, support the construction of Ferrogrão (Grainrail), a railway wanted badly by agribusiness and being fast tracked by the Bolsonaro administration that would cut through the heart of the Amazon rainforest. The project is strongly opposed by Indigenous peoples and many environmentalists.

“The recent efforts to unblock rail infrastructure in Brasil, especially in the North region, are fundamental for agriculture,” the report reads. “Beyond Ferrogrão, the conclusion of the North-South railway in the state of Pará is important to encourage sustainability in the agricultural sector.”

According to Astrini, any Amazon infrastructure project needs to proceed with great caution, following the premise that the region has weak socio-environmental governance. “Throughout the Amazon’s history, wherever infrastructure projects are implemented, you see an increase in pressure for land and forest loss,” he told Mongabay.

A March 2020 study by the Climate Policy Initiative’s Brazil Policy Center found that Brazil could lose 2,043 square kilometers (788 square miles) of native vegetation if Grainrail is built.

But according to the National Logistics Plan for 2025, the implementation of railways and other infrastructure projects could reduce transportation costs by US $9.9 billion a year and reduce Brazil’s total carbon emissions by 14.3%.

Other WRI proposals, such as a shift to cleaner fossil fuels in the aviation industry, seem unlikely to be adopted, given the economic hit the sector has taken due to the pandemic, says Maimon.

“It’s a great start and showing a path for the country, but there is a lot more that still needs to be done,” said Maimon.

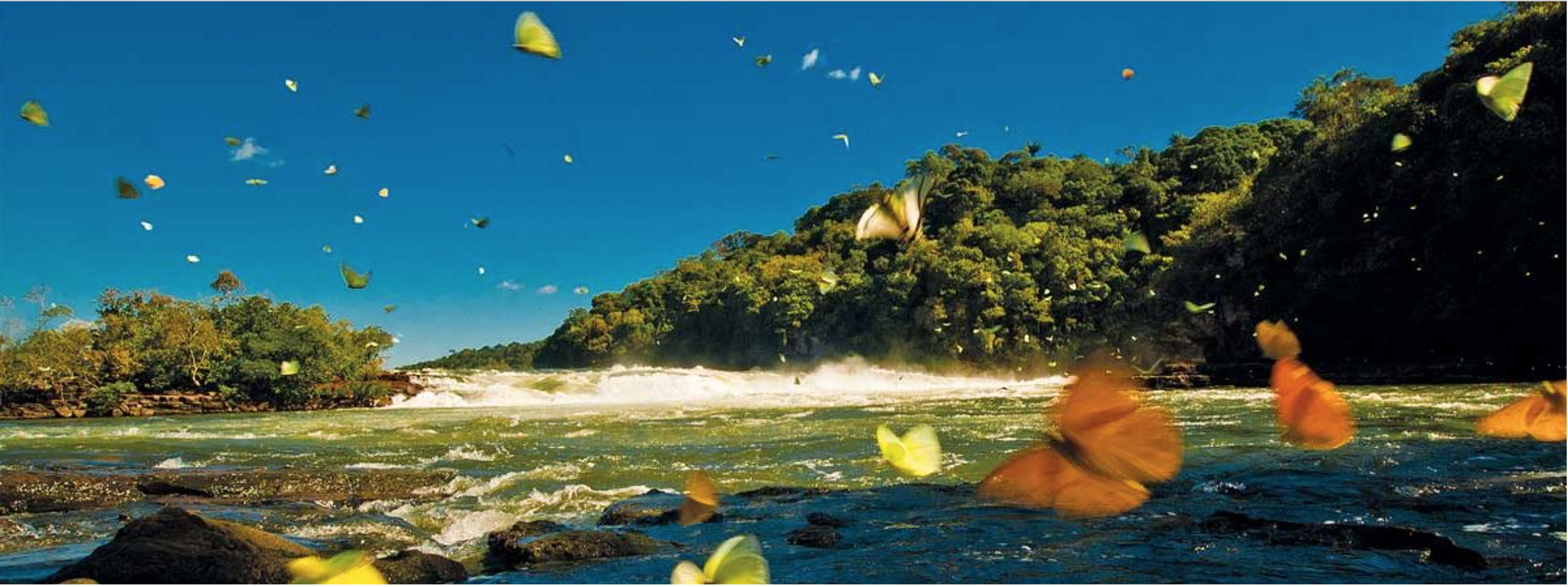

Banner image: Butterflies over the Amazon’s Juruena River. Image © Fernando Lessa / The Nature Conservancy.

FEEDBACK: Use this form to send a message to the author of this post. If you want to post a public comment, you can do that at the bottom of the page.

Leave A Comment