When Manoel Baião discusses the business climate in Brazil, the chief executive speaks in colourful meteorological metaphors: Latin America’s biggest economy has for years been buffeted by storms, he said, but the dark clouds are finally — gradually — beginning to clear.

“The last two years have been a period of waiting [but] now I feel, not only on the part of Brazilian businessmen but also in the international business community, a great desire for this to work,” said Mr Baião, who heads up Neolink International, a business development group.

The executive’s comments reflect a “cautious optimism” that has taken hold in Brazilian business circles since the election of President Jair Bolsonaro in October and the appointment of Paulo Guedes, a free-market evangelist, as economics minister.

Despite several formidable obstacles, including attempts to pass a vital pensions reform billthrough Congress, many businesses are quietly confident that Brazil is poised for an upswing after years of sluggish growth following the worst recession in the nation’s history.

“We are coming from a very difficult recent past with the recession and the various corruption investigations,” said Marianna Waltz, managing director for Latin American corporates at Moody’s, referring to the Lava Jato, or Car Wash, probe that implicated vast swaths of Brazil’s corporate establishment. Fernando Musa, Braskem chief

“It really seems now we have a more stable environment at least. We are going to see the country grow independent of what happens in politics at least over the next couple of years,” said Ms Waltz, who manages a portfolio of the nation’s largest companies, including Petrobras and Embraer.

The sunny outlook is bolstered by healthy earnings reports across many sectors. Last year reported profits of companies listed on São Paulo’s B3 stock exchange reached R177bn ($45bn), up 40 per cent from R125bn the previous year, according to data from Economatica.

Add to that mix state-owned energy companies Petrobras and Eletrobras, as well as telecoms Oi, and combined corporate profits hit 241bn reals last year, an increase of more than 100 per cent from R116bn in 2017 when the brutal two-year recession ended.

“With the recession and the corruption investigations, all the companies were under pressure. They were forced to adjust, to reduce capex and costs and to reorganise to a new market situation. So now companies are very well positioned in terms of credit metrics and we are seeing a continuous deleveraging trend and improving liquidity,” said Ms Waltz.

“We think the companies are in a very good situation. Investors are seeing that as well.”

Such rhetoric has been backed up by an impressive market rally. The benchmark Bovespa index

touched a historic high of 100,000 points last month.

Since then it has fallen to about 97,000 points as political bickering between Mr Bolsonaro and Congress fuels concern that the new administration will be unable to pass a pensions reform bill, widely seen as crucial to kick-start the economy.

Spearheaded by Mr Guedes, the reform seeks to tackle Brazil’s precarious fiscal position by reducing pensions payments by R1tn.

But it has a deeper significance: Domestic and international companies and investors have latched on to the passage of the bill as a test case of whether the new administration will be able to pass its broader reform agenda, including privatisations and deregulation.

“Investment decisions are waiting for pension reform,” said David Beker, chief Brazil economist at Bank of America Merrill Lynch.

“From my conversations, businesses are willing to wait and eventually deploy more capital. Get the reform done and you will have a transformation.”

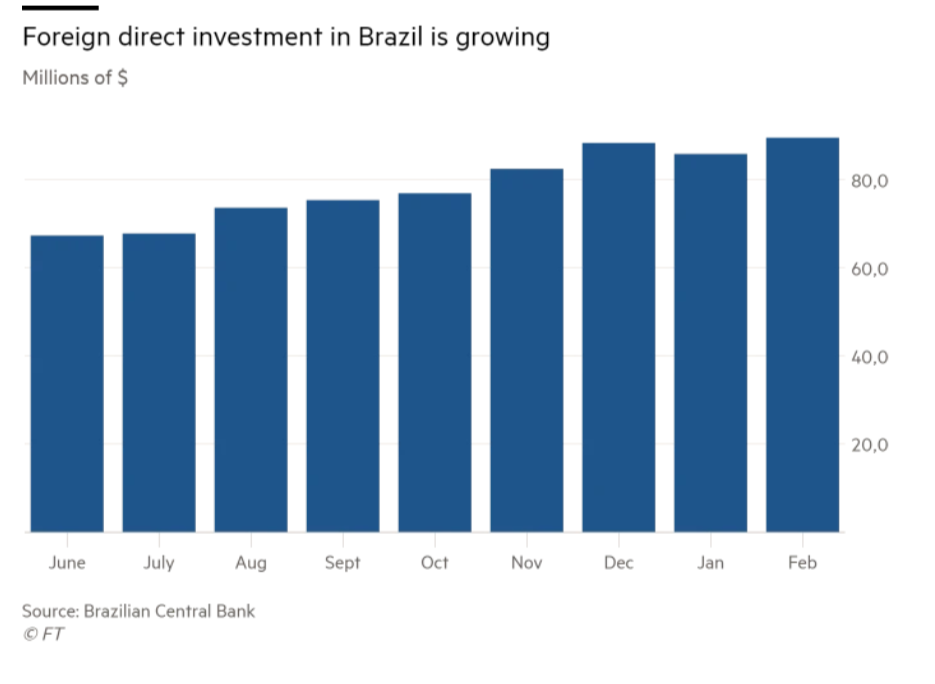

In the 12 months to February, foreign direct investment in Brazil reached $89.5bn, up from $67.7bn the previous year, according to the central bank.

Analysts, however, have cautioned that historically almost half the money reported as FDI in Brazil was in fact company loans between overseas companies and their Brazilian arms and reinvested profits.

“There is optimism. The new government has signalled a liberal agenda with the large participation of the private sector through privatisations and concessions,” said Otávio Guazzelli, a managing director of Moelis Brazil.

“[But] reforms are essential, if this does not really happen or happen in a very timid manner, it may have a huge expectation reversal in the market.”

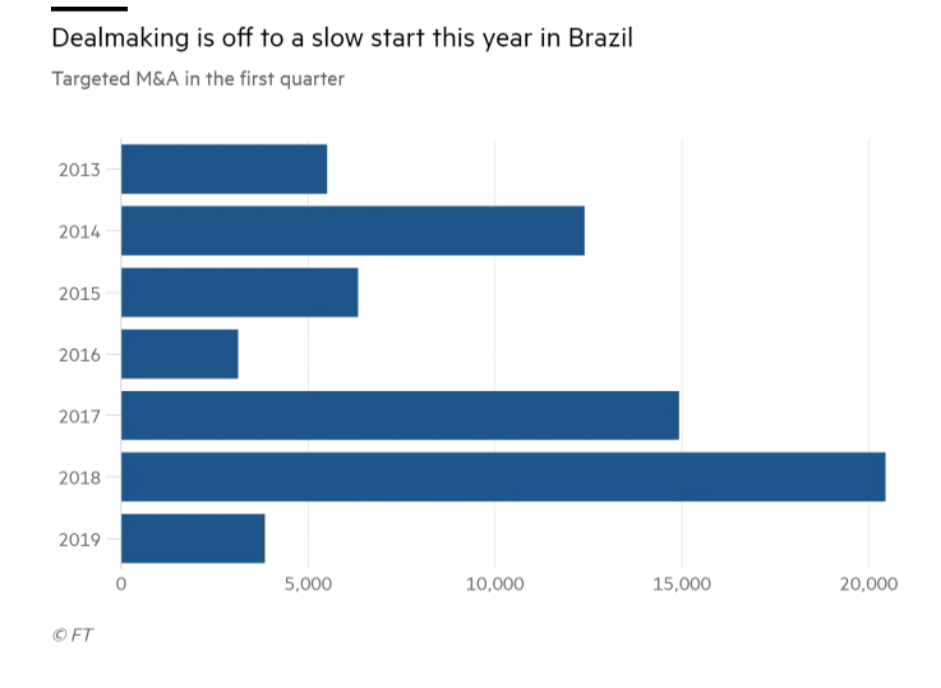

A more cautious sign, however, has been the dearth of mergers and acquisitions. By number of deals, 2019 has seen the slowest start to a year since 2005, according to Dealogic. By deal value, it has been the second slowest since 2005, the data provider said.

Several other metrics have also weighed on the broader outlook. Unemployment of more than 12 per cent continues to act as a damp on consumption, while a recovery in industrial production has been softer than analysts had forecast.

A study released this month found that Brazilian industry now accounts for the smallest portion of GDP in 70 years.

“With nothing pushing demand or growth too hard, it will be more of a gradual process. Unemployment rates are still high [and] it will take time to see capacity and production levels coming back to levels [witnessed] in previous years,” said Ms Waltz at Moody’s.

Fernando Musa, chief executive of petrochemicals group Braskem, echoes a common refrain in corporate circles when he calls for a patient approach to reforms.

“Competitiveness in Brazil is measured in decades, not in the next three months,” he said. “The important thing is to be on the right track. I think we are.”

Copyright The Financial Times Limited 2019. All rights reserved.

Leave A Comment